The Story of Legendary Sword Fisherman Ted Naftzger, Jr.

By Gary Graham

Men often fight monsters, both in fairy tales and in real life … sometimes by fate and sometimes by choice.

Men often fight monsters, both in fairy tales and in real life … sometimes by fate and sometimes by choice.

R.E. (Roy E.) “Ted” Naftzger, Jr. and the monsters he chose as adversaries were swordfish in Southern California, black marlin at Lizard Island and giant bluefin tuna on the East Coast.

A California native, Naftzger graduated from Stanford in 1946, received a degree in history from the University of Southern California in 1948 and ultimately a master’s in 1986. A cattle rancher, as well as a highly respected numismatist of some 60 years and a world-class angler, he passed away on Oct. 29, 2007. He was 82. Naftzger was survived by his wife, Pauline; three daughters, Natalie Davis, Sandra Dritley and Nancy; plus six grandchildren.

His contributions to recreational angling were extraordinary. He was inducted into the IGFA Hall of Fame, was an IGFA trustee from 1979 to 2002 and served as IGFA board secretary from 1986 to 2001. In 1994, he received IGFA’s Elwood K. Harry Fellowship Award in honor of his lifelong contributions to recreational angling.

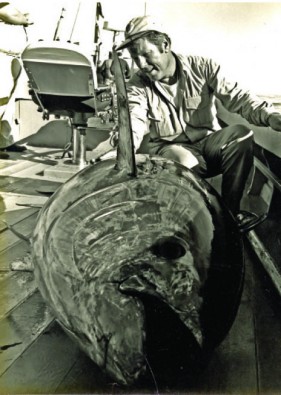

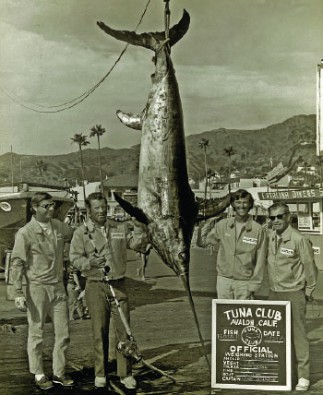

He still holds a Tuna Club record set in 1970 for a 503-pound broadbill swordfish on 80-pound Dacron line, and he remains in the record books in Massachusetts for a 131-pound white marlin caught off Nantucket in 1982. Naftzger was president of the Tuna Club of Avalon, and was a founding member of the Channel Island Broadbill Tournament as well as the Lizard Island Fishing Club. He was a member of the U.S. team at the International Tuna Cup Matches from 1967 to 1970, capturing first place twice.

And though Ted Naftzger has successfully fished for exciting game fish all over the world, spending many seasons on the Great Barrier Reef, it’s his sword fishing skills that are legendary. He caught 49 swordfish on California boat or crew, let alone single angler, who managed to accomplish such a feat. However, one man, Roy E. Naftzger, Jr., or “Ted” to his friends, did just that.

“I remember Ted as the ultimate gentlemen’s gentleman,” said Michael Leech, IGFA executive director from 1983-1993. “He was definitely one of our sport’s true legends. Once we lost Ted, the art of surface sword fishing seems to have been lost. His kind of sportsmanship is hard to find in this day and age. I miss him.”

Naftzger’s angling accomplishments aboard his Rybovich locally, as well as internationally, are remarkable examples of tenacity and dedication to his sport.

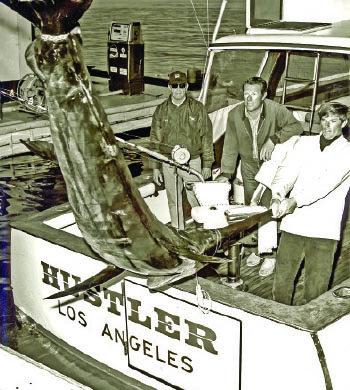

It was more than a half-century ago when he purchased his first Rybovich and his passion for catching swordfish on rod and reel began. Shipping her to Los Angeles, he renamed her Hustler and hired Captain Art Cherry to run her. At that time, most West Coast anglers ignored swordfish, preferring less difficult, more common, striped marlin. However, his new captain possessed extensive knowledge on baiting broadbill on the East Coast; Ted Naftzger decided to apply similar techniques in the Pacific and the rest is history.

Beginning in 1963 until he stopped his quest, he baited those 49 swords on the surface, catching this most difficult saltwater sportfish during daylight hours, earning him the title of “Master of Daytime Sword Fishing.” To Naftzger, sword fishing was a passion, and he had few peers in this often humbling and frustrating sport.

Speaking with his friends, associates, peers, and admirers not only provided a glimpse into Naftzger but, on a grander scale, a subtle overview of the anglers, techniques and resources that existed in an era that many claim is lost forever.

When Naftzger, along with Al Carlton and Jerry Garrett, teamed up with Bud Smith (Mr. Oxnard) to put on the first Channel Islands Invitational Broadbill Tournament in 1972, the first year’s statistics reflect what an immense fishery it was compared to now. Results included reports of 300 broadbill spotted, more than 75 baited and approximately 50 hooked up. Yet only 16 swordfish were landed, the largest weighing 454 ½ pounds.

The swordfish was notoriously difficult to tempt with baits on the surface and extremely hard to hook; when hooked, its strength, determination and fury are legendary. Stories abound of anglers battling swordfish for entire days and then of it turning mid-fight and attacking boats. Naftzger’s passion for swordfish grew precisely because of the degree of difficulty and challenge of the fight. These were the things that legends were made of.

The swordfish was notoriously difficult to tempt with baits on the surface and extremely hard to hook; when hooked, its strength, determination and fury are legendary. Stories abound of anglers battling swordfish for entire days and then of it turning mid-fight and attacking boats. Naftzger’s passion for swordfish grew precisely because of the degree of difficulty and challenge of the fight. These were the things that legends were made of.

He ran a no-nonsense operation with little radio chatter and he seldom invited anyone aboard his beloved, very-fast, gas-powered, 37-footer. Cherry, his captain for decades, and his crew always wore khaki uniforms. It was as though they were dressed for battle. Single-purposed, he ignored marlin for the most part, often calling one of his friends close by if his crew spotted a marlin.

Though his close friends understood his intense determination, some of his contemporaries were confounded over the years by his passion for privacy. Many revealed their ignorance of the man, preferring to use a variety of adjectives describing him as a loner, aloof, odd, interesting and unusual.

Shy, he seldom shared his on-the-water adventures with outsiders, preferring to save those stories for the close circle of fellow fishermen he admired. He reveled in their fishing conquests and many still have cherished personal hand-written notes commending them for their angling accomplishments.

After a day of fishing Southern California waters, Naftzger often stayed on a mooring at Avalon. He would visit the Tuna Club, going upstairs to his favorite corner room overlooking the harbor, preferring not to mingle. Naftzger jogged daily whether from his home in Beverly Hills or in Avalon, often before departing for the day’s fishing.

Always prepared, he had several sets of Daytona gasoline engines stashed in three different ports in case the Hustler’s failed. He did not want to miss a day’s fishing.

Once, Naftzger spotted Don McPherson, who was alone aboard his Boston Whaler on the 499, hooked up to a two-finner. Naftzger immediately ran to his friend, remaining with him for hours until the foul-hooked fish unfortunately pulled free.

The last time Dave Denholm, friend and fellow Tuna Club member, spoke to Naftzger was when he caught his 452.5-pound sword near the 499 one morning; this is the standing California State Record. Apparently records were not being maintained during Naftzger’s earlier accomplishments.

Dave proudly admitted, “My first call from the Espadon was to Ted at his office in Beverly Hills. He graciously congratulated me and wanted to hear the blow-by-blow details. I felt I wanted to talk to Ted at that moment as our ‘sword’ bond was truly a rare link of mutual respect for an unusual passion and sharing that success with my mentor seemed essential. Ted followed up with a congratulatory long-hand note as was his custom.”

Jerry Garrett, another friend and Tuna Club member, proudly displays a similar note in his trophy room in New Zealand!

Jerry Garrett, another friend and Tuna Club member, proudly displays a similar note in his trophy room in New Zealand!

Every November, Naftzger would journey to Cairns, Lizard Island, Australia, to fish for black marlin. Over the years, he and his friends caught and released many “granders.”

Denholm recalls those trips fondly. “Both of us had a number of ‘granders’ to our credit and another friend, Kay Holland, caught one on 50-pound test line. He also fished Ted’s other boat in the Azores with great success.”

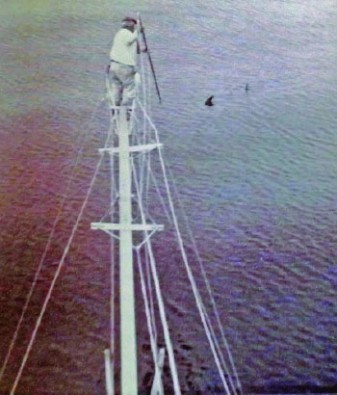

As Naftzger’s swordfish count grew, speculation of his methods and techniques grew among Southern California anglers as well. As is often the case, the conjecture exchanged via obscure VHF radio channels became more ludicrous with each new catch.

Naftzger advanced a few “presentation” approaches he liked when eyeballing a sword, but there were very few absolutes that he knew of or could rely on in his search.

However, that didn’t deter the “wannabes” searching for some “secret sauce.” When the Hustler would appear on the horizon, Ziess binoculars turned toward her. Anglers who spotted her were gratified, believing they were in the right zone. “Look’ their riggers are longer,” they would state. “What is that they are trolling? Is that a bent-butt rod in the rod holder on the chair?” And so on …

According to Denholm, the long outriggers were typical of many East Coast Rybos and Merritts. All but one of his swords was caught on presented rigged squid baits. Naftzger played with a lot of twists to the presentation but at the end of the day, the answer was focus, patience and dedication with tunnel vision.

Drive by the marlin to get to the swordfish areas, bait as many as you can find, in any way you can, and some will eat.

Bill McWethy tells a story of fishing with Naftzger and Felix McGinnis many years ago aboard his C Bandit. In the gray light, they spotted a group of sleepers. McWethy hollered for the two anglers to go to the bow to cast. Both admitted that they couldn’t cast … so they slow-trolled the baits to the sleepers.

This would explain why Naftzger chose to present a bait from an outrigger. The sword could eat from behind instead of chasing down a squirrelly, live mackerel, resulting in a higher percentage of mouth-hooked fish versus foul-hooked fish. Then, if all worked out, Naftzger was already in a fighting chair (no stand-up) with bent butt working for him. He was an excellent angler (maybe the best) using that set up. Hustler could spin on a dime, completing the perfect combo to do battle with a top-notch crew to boot.

Obviously, to accomplish catch numbers in the double-digits, there were many losses along the way. There is a story of Naftzger hooking up in the lee of Clemente one afternoon only to lose the fish off the Tijuana Bull Ring the following afternoon, which accentuates Naftzger’s stamina and tenacity, his ability to hang in there regardless.

Obviously, to accomplish catch numbers in the double-digits, there were many losses along the way. There is a story of Naftzger hooking up in the lee of Clemente one afternoon only to lose the fish off the Tijuana Bull Ring the following afternoon, which accentuates Naftzger’s stamina and tenacity, his ability to hang in there regardless.

Ted Naftzger’s 48th swordfish came after a nine-year drought between the 47th and 48th.

“I’ve been out several times a year,” he lamented, “once or twice a week in the summertime.”

Naftzger finally broke his slump on Sunday, Nov. 21, 1993, when he took his 48th monster on the west side of Santa Monica Bay about 10 miles off the beach. He had taken his boat to the Channel Islands to look for swordfish over the weekend and after a fruitless, two-day search headed home in a cold, miserable, flat-calm drizzle.

About 2 p.m., as the boat approached one of the deepest spots in the bay, the 503-Fathom Spot, Naftzger’s boat captain, Tom Furtado of Florida, spotted the sword cruising on the surface. Naftzger snatched the Spanish mackerel he had in his live well for three weeks.

About 2 p.m., as the boat approached one of the deepest spots in the bay, the 503-Fathom Spot, Naftzger’s boat captain, Tom Furtado of Florida, spotted the sword cruising on the surface. Naftzger snatched the Spanish mackerel he had in his live well for three weeks.

“I hooked it on a 50-pound outfit and the swordfish ate it,” Naftzger said. “The fish was very active … jumped several times and made one real long run, which was thrilling to see. It cleared the water doing a scissor-jump, where they almost touch their bill to their tail.”

Within 45 minutes, Naftzger had it to the boat. A triple-flag fish: first of the year caught by one person for the Avalon Tuna Club, the Balboa Angling Club and the Newport Harbor Yacht Club. The sword weighed 234 pounds.

“I’ve been hitting them for 30 years, every chance I could,” he remarked. “But it’s like big-game hunting, except on the ocean. You’re hunting for one individual fish.”

Records of the Tuna Club, the oldest sportfishing club, showed that this was only the second swordfish caught by a member since 1986 and the seventh since 1978.

Records of the Tuna Club, the oldest sportfishing club, showed that this was only the second swordfish caught by a member since 1986 and the seventh since 1978.

“They’ve been depleted pretty heavily by commercials,” Naftzger said, “especially the driftnets and longliners.”

Over the years, with more sport boats, stick boats and airplanes in common fishing grounds, presenting baits from an outrigger that requires “room to maneuver” also required some sense of etiquette from nearby fishermen to give an angler some room.

“Between curiosity seekers, stick boats and other traffic, it has become much harder and harder to manage a proper outrigger presentation … hence, the preferred approach of casting live mackerel to ensure at least a few clean presentations,” Denholm observed. “We had our learning curve and do present a cast bait a certain way that we believe produces the best results.”

“We were good pals; Ted was the epitome of the Gentleman Angler,” Denholm remembered. “A rare breed indeed.”

When inducted into the IGFA Hall of Fame in 2002, Naftzger’s 49 swordfish, according to the organization’s website, was a record that has never been duplicated on the West Coast.

When Naftzger died in 2007, his dream of that 50th broadbill had never faded. His true passion for swordfish on rod and reel remained with him until his death. In his own words: “The hunt for swordfish is absolutely magnificent. You take your boat and search the surface of the ocean for your quarry, constantly testing your mental ability to solve one of nature’s closely guarded secrets. It’s precisely this challenge that keeps me coming back. If it were easy, I just wouldn’t do it.”

Red sky filled the horizon to the east as we slowly motored down the 40-fathom ridge. The Furuno split screen was set on both plotter and depth, and I was looking for “the corner” on the southwest side of the ridge where the hard bottom area turns toward the beach. The 63-degree, clean, blue water confirmed what the SST (sea surface temperature) and chlorophyll (plankton) charts reported the previous night. There were just a handful of private boats this early and about 90 percent of them were following a couple sportboats around that were making their first tacks with the sonar.

Red sky filled the horizon to the east as we slowly motored down the 40-fathom ridge. The Furuno split screen was set on both plotter and depth, and I was looking for “the corner” on the southwest side of the ridge where the hard bottom area turns toward the beach. The 63-degree, clean, blue water confirmed what the SST (sea surface temperature) and chlorophyll (plankton) charts reported the previous night. There were just a handful of private boats this early and about 90 percent of them were following a couple sportboats around that were making their first tacks with the sonar.

If you have done your homework on an area, being able to read the contours and find small isolated stones or structure within a hard bottom area is the key to success. I keep my eyes glued to the plotter and sounder and hit MOB anytime I mark an area of interest. As you slowly work up and down an area, it’s like connecting the dots on the plotter and eventually you are going to stumble over a school of fish. If you are not marking fish but seeing good signs of bait and structure on the sounder,consider a blind drift. My boat partner did just that on a recent client trip and put two fat yellowtail onboard on his first drift.

If you have done your homework on an area, being able to read the contours and find small isolated stones or structure within a hard bottom area is the key to success. I keep my eyes glued to the plotter and sounder and hit MOB anytime I mark an area of interest. As you slowly work up and down an area, it’s like connecting the dots on the plotter and eventually you are going to stumble over a school of fish. If you are not marking fish but seeing good signs of bait and structure on the sounder,consider a blind drift. My boat partner did just that on a recent client trip and put two fat yellowtail onboard on his first drift.

There are several ways to rig live baits for fishing down to 50 fathoms. On a sportboat, the reversed dropper loop is best at these depths and the standard dropper loop rig works well in the shallower spots (20 fathoms or less) where there is less of a chance to hook rockfish.

There are several ways to rig live baits for fishing down to 50 fathoms. On a sportboat, the reversed dropper loop is best at these depths and the standard dropper loop rig works well in the shallower spots (20 fathoms or less) where there is less of a chance to hook rockfish. My first exposure to fishing the hard bait, or jerk bait as it’s known in fresh water, came while targeting largemouth bass at Pyramid Lake some 10 years ago with Marc Higashi of Performance Tackle in Los Alamitos. “It’s a simple bait to fish,” Higashi explained when we arrived at our first spot that morning. “Just cast it out and retrieve it using a wind, wind, jerk, pause cadence.” To illustrate this, he cast the lure along the shoreline and, using a combination of sporadic turns of the reel handle coupled with well timed twitches of the rod tip, made the bait swim enticingly just below the surface.

My first exposure to fishing the hard bait, or jerk bait as it’s known in fresh water, came while targeting largemouth bass at Pyramid Lake some 10 years ago with Marc Higashi of Performance Tackle in Los Alamitos. “It’s a simple bait to fish,” Higashi explained when we arrived at our first spot that morning. “Just cast it out and retrieve it using a wind, wind, jerk, pause cadence.” To illustrate this, he cast the lure along the shoreline and, using a combination of sporadic turns of the reel handle coupled with well timed twitches of the rod tip, made the bait swim enticingly just below the surface.

I’ll spare you the details of my day, but will say that after several hours of jerking, twitching, lurching and much frothing of the water for not a single bite, I again admitted defeat. Several days later, and once the muscle spasms in my right arm relaxed enough for me to use my hand, I picked up the phone and called my friend and Lucky Craft pro-staffer Chris Lilis for help.

I’ll spare you the details of my day, but will say that after several hours of jerking, twitching, lurching and much frothing of the water for not a single bite, I again admitted defeat. Several days later, and once the muscle spasms in my right arm relaxed enough for me to use my hand, I picked up the phone and called my friend and Lucky Craft pro-staffer Chris Lilis for help. He continued: “One of the biggest parts of fishing any of these baits effectively is matching them up with the right rod-and-reel combo. The smaller baits I fish are the Pointer 128 and the Flash Minnow 130, and my go to color is American Shad. Both of these baits can be fished on a 7-8 foot medium heavy graphite rod; I fish a Performance Tackle 707MH matched with an Abu Garcia Revo Inshore full of 50-pound Spiderwire braid.

He continued: “One of the biggest parts of fishing any of these baits effectively is matching them up with the right rod-and-reel combo. The smaller baits I fish are the Pointer 128 and the Flash Minnow 130, and my go to color is American Shad. Both of these baits can be fished on a 7-8 foot medium heavy graphite rod; I fish a Performance Tackle 707MH matched with an Abu Garcia Revo Inshore full of 50-pound Spiderwire braid.

Trusting our preconceived notions is one of the biggest stumbling blocks we face as developing anglers. To make matters worse, the more we develop as anglers, the more likely we are to trust our preconceived notions and in turn, trip ourselves up. While this vicious cycle can take a variety of forms, all of them result in the same: missed angling opportunities.

Trusting our preconceived notions is one of the biggest stumbling blocks we face as developing anglers. To make matters worse, the more we develop as anglers, the more likely we are to trust our preconceived notions and in turn, trip ourselves up. While this vicious cycle can take a variety of forms, all of them result in the same: missed angling opportunities.

Things started off just as I expected, with tiny calicos biting the small swimbaits we were throwing. But as we progressed along the wall and got our baits and presentations dialed in, the fish started getting bigger. Once we had five fish in the tank, we further refined our presentations and began to cull out our smaller fish.

Things started off just as I expected, with tiny calicos biting the small swimbaits we were throwing. But as we progressed along the wall and got our baits and presentations dialed in, the fish started getting bigger. Once we had five fish in the tank, we further refined our presentations and began to cull out our smaller fish.

Joining me on the trip was Eric Bent, tournament director of the SWBA and an avowed embracer of “old school” fishing techniques. As a counterpoint to Bent’s conventional style, I invited Abu Garcia pro staffer Chris Lilis, who is always on the forefront of tackle and bait technology. As for me, I just brought my camera and left my preconceived notions at the dock.

Joining me on the trip was Eric Bent, tournament director of the SWBA and an avowed embracer of “old school” fishing techniques. As a counterpoint to Bent’s conventional style, I invited Abu Garcia pro staffer Chris Lilis, who is always on the forefront of tackle and bait technology. As for me, I just brought my camera and left my preconceived notions at the dock.

Lilis continued, “In the outer harbor, you’re basically looking for riprap that’s getting surge or has wind blowing against it. This stuff fishes very similar to how the break wall does. Bass are going to be around the areas with surge, looking for baitfish that are getting pushed against the rocks or crabs that are being knocked free.

Lilis continued, “In the outer harbor, you’re basically looking for riprap that’s getting surge or has wind blowing against it. This stuff fishes very similar to how the break wall does. Bass are going to be around the areas with surge, looking for baitfish that are getting pushed against the rocks or crabs that are being knocked free.

After catching another sand bass on the spinnerbait, Bent went back to his previous technique; this time with a purple Texas rigged tube. “There are some big spotted bay bass in the outer harbor and I’m hoping I can get one to bite this slower presentation,” Bent said moments before swinging on a heavy fish. The fish pulled hard, but ended up being a jumbo sculpin, instead of a spotty. Bent managed several more plus-sized sculpin over the next few minutes before eventually getting broken off by something that fought like the spotty he’d been looking for.

After catching another sand bass on the spinnerbait, Bent went back to his previous technique; this time with a purple Texas rigged tube. “There are some big spotted bay bass in the outer harbor and I’m hoping I can get one to bite this slower presentation,” Bent said moments before swinging on a heavy fish. The fish pulled hard, but ended up being a jumbo sculpin, instead of a spotty. Bent managed several more plus-sized sculpin over the next few minutes before eventually getting broken off by something that fought like the spotty he’d been looking for.

This season the first two trips deep into southern waters were made by Polaris Supreme and Intrepid, in early October. The fish were there, at the Hurricane Bank and the Buffer Zone, and both boats had success catching wahoo, big tuna and numerous cows, tuna over 200 pounds.

This season the first two trips deep into southern waters were made by Polaris Supreme and Intrepid, in early October. The fish were there, at the Hurricane Bank and the Buffer Zone, and both boats had success catching wahoo, big tuna and numerous cows, tuna over 200 pounds. Winter Wonderland

Winter Wonderland

I never thought that trolling a dead black skipjack on the surface just 20 feet from the transom and rolling over like a plug-cut sardine would entice anything. Especially when run next to some precision-rigged, bridled livies swimming strongly below the surface where they should be. Yet, at 10:30 a.m. on this September day at the Hannibal Bank in the calm Gulf of Chiriqui, Panama, this all changed as a huge “whooshing” noise and foaming swirl startled a crew from the Panama Big Game Fishing Club.

I never thought that trolling a dead black skipjack on the surface just 20 feet from the transom and rolling over like a plug-cut sardine would entice anything. Especially when run next to some precision-rigged, bridled livies swimming strongly below the surface where they should be. Yet, at 10:30 a.m. on this September day at the Hannibal Bank in the calm Gulf of Chiriqui, Panama, this all changed as a huge “whooshing” noise and foaming swirl startled a crew from the Panama Big Game Fishing Club. The bait disappeared and then popped up again. Mate Michael Rios quickly dropped it back, free-lining it as if it were falling naturally. The spool started to spin again and Florida angler Ralph Collazo set the circle hook and was pulled to the transom and finally made it to the fighting chair of the 31-foot Bertram. “This isn’t like the sailfish I catch off Ft. Lauderdale,” he yelled out.

The bait disappeared and then popped up again. Mate Michael Rios quickly dropped it back, free-lining it as if it were falling naturally. The spool started to spin again and Florida angler Ralph Collazo set the circle hook and was pulled to the transom and finally made it to the fighting chair of the 31-foot Bertram. “This isn’t like the sailfish I catch off Ft. Lauderdale,” he yelled out. The Republic of Panama boasts a wide variety of gamefish, and visiting anglers have doubled in number since 2001. A unique combination of oceanic currents, islands, seamounts and a meandering continental shelf creates a year-round habitat for gamefish that respond well to a variety of fishing techniques—exactly what an angler wants in a fishery. Whether you like to cast surface poppers, deep jig, troll bait and lures or fly fish, Panama is a good place to hone your skills or try new techniques where the fish are more likely to respond to your presentation.

The Republic of Panama boasts a wide variety of gamefish, and visiting anglers have doubled in number since 2001. A unique combination of oceanic currents, islands, seamounts and a meandering continental shelf creates a year-round habitat for gamefish that respond well to a variety of fishing techniques—exactly what an angler wants in a fishery. Whether you like to cast surface poppers, deep jig, troll bait and lures or fly fish, Panama is a good place to hone your skills or try new techniques where the fish are more likely to respond to your presentation.

Marlin and tuna may have put Panama on the international map but the inshore and island game fish are the backbone of the year-round fishery. It’s not unusual to record 20 to 30 species during a week if you try different techniques and a variety of habitats. As in other world-class fisheries, Panama is concerned about sustainability of the resource among competing interests. The Big Game Fishing Club is a supporter of the newly formed Panama Marine Resource Foundation under President John Maynard that seeks to have a stronger voice in the politics of fishery management. The PMRF has put together a draft of “common sense” rules for sportfishing that include the release of all marlin, sailfish, roosterfish, grouper and cubera snapper while creating a size and species limit on dorado, wahoo and other species.

Marlin and tuna may have put Panama on the international map but the inshore and island game fish are the backbone of the year-round fishery. It’s not unusual to record 20 to 30 species during a week if you try different techniques and a variety of habitats. As in other world-class fisheries, Panama is concerned about sustainability of the resource among competing interests. The Big Game Fishing Club is a supporter of the newly formed Panama Marine Resource Foundation under President John Maynard that seeks to have a stronger voice in the politics of fishery management. The PMRF has put together a draft of “common sense” rules for sportfishing that include the release of all marlin, sailfish, roosterfish, grouper and cubera snapper while creating a size and species limit on dorado, wahoo and other species.

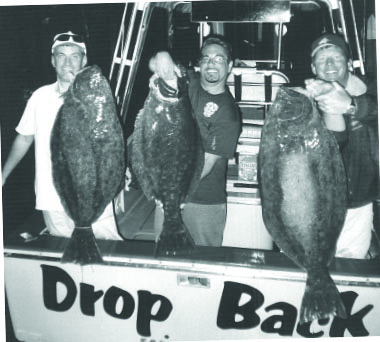

With the approach of summer, California halibut are slowly moving into the medium water depths to fatten up before working into the shallows to spawn. This fishery has made a huge comeback and now 40 pounders are fairly commonplace throughout the state—so maybe you’ll get to check that one off your bucket list.

With the approach of summer, California halibut are slowly moving into the medium water depths to fatten up before working into the shallows to spawn. This fishery has made a huge comeback and now 40 pounders are fairly commonplace throughout the state—so maybe you’ll get to check that one off your bucket list.

As noted, for the last few years we have been blessed with a huge influx of squid to the California coast and a boon to the recent comeback in the halibut population, adding to the forage base of various fin bait. This has really produced a bigger volume of these larger model halibut which grow into the breeders that produce huge amounts of eggs. The widespread availability of the cephalopods gives us many different areas to target. The market squid that bed up on our California coast can land just about anywhere, typically bedding up in 60 to 120 feet along the coast.

As noted, for the last few years we have been blessed with a huge influx of squid to the California coast and a boon to the recent comeback in the halibut population, adding to the forage base of various fin bait. This has really produced a bigger volume of these larger model halibut which grow into the breeders that produce huge amounts of eggs. The widespread availability of the cephalopods gives us many different areas to target. The market squid that bed up on our California coast can land just about anywhere, typically bedding up in 60 to 120 feet along the coast.

This brings up another long-debated subject among halibut fishermen: the trap hook. Many add a treble hook to the tail end of the baitfish, be it a mackerel, sardine or anchovy. This in an attempt to get those aforementioned short biters. But let’s play out a halibut bite in words: Your bait comes across the top of a halibut sitting along the sandy bottom. When the fish strikes it is with a powerful aggressive maneuver and will normally go straight back to the bottom.

This brings up another long-debated subject among halibut fishermen: the trap hook. Many add a treble hook to the tail end of the baitfish, be it a mackerel, sardine or anchovy. This in an attempt to get those aforementioned short biters. But let’s play out a halibut bite in words: Your bait comes across the top of a halibut sitting along the sandy bottom. When the fish strikes it is with a powerful aggressive maneuver and will normally go straight back to the bottom.

The Gray Ghost. A lot can be said about a fish by the nicknames we choose to give it. These elusive croakers slide in and out of coastal areas, only subtly making their presence known. One of the only clues we have, especially this time of year, is when the market squid finally starts to float and bed in our warming coastal waters. Whether you made it out to the islands on a mothership, or are beach launching your kayak from the mainland, the white seabass is one of the inshore trophies you don’t want to miss.

The Gray Ghost. A lot can be said about a fish by the nicknames we choose to give it. These elusive croakers slide in and out of coastal areas, only subtly making their presence known. One of the only clues we have, especially this time of year, is when the market squid finally starts to float and bed in our warming coastal waters. Whether you made it out to the islands on a mothership, or are beach launching your kayak from the mainland, the white seabass is one of the inshore trophies you don’t want to miss.

I like to use one of my kelp cutter rigs for this style of fishing. Since we’re mostly fishing on the edge of the kelp, 60-pound braided line tied to a 30-pound fluorocarbon leader will help you saw your way out of the kelp, while also putting the line-shy white seabass at ease. Some guys like using mono here, but their sharp gill plate can really start to grind away at the leader, so the more abrasion resistant the better. Nose hook the mackerel with a 2/0-4/0 sized circle hook. It’s nice to have a second rig here to tie in a sliding sinker. There’s no telling what part of the water column the white seabass will want to bite so be prepared to change if the conditions tell you to.

I like to use one of my kelp cutter rigs for this style of fishing. Since we’re mostly fishing on the edge of the kelp, 60-pound braided line tied to a 30-pound fluorocarbon leader will help you saw your way out of the kelp, while also putting the line-shy white seabass at ease. Some guys like using mono here, but their sharp gill plate can really start to grind away at the leader, so the more abrasion resistant the better. Nose hook the mackerel with a 2/0-4/0 sized circle hook. It’s nice to have a second rig here to tie in a sliding sinker. There’s no telling what part of the water column the white seabass will want to bite so be prepared to change if the conditions tell you to. Fresh dead squid is another good option for kayakers. If I decide to dead stick a rod, I will pin two of them onto an iron and set it just off the bottom with a light drag. The natural rocking of the kayak will bring those dead squid back to life as they lift up and fall back down.

Fresh dead squid is another good option for kayakers. If I decide to dead stick a rod, I will pin two of them onto an iron and set it just off the bottom with a light drag. The natural rocking of the kayak will bring those dead squid back to life as they lift up and fall back down.

If there’s a trolling jig that’s a universal soldier, it must be the cedar plug. No other jig seems to match its strong kicking action, which looks like a sardine in a serious hurry to reach safer parts. All tuna, even the jig-shy bluefin, will bite it, and so will marlin, wahoo, yellowtail, bonito, dorado, grouper, cabrilla, snapper and ambitious mackerel.

If there’s a trolling jig that’s a universal soldier, it must be the cedar plug. No other jig seems to match its strong kicking action, which looks like a sardine in a serious hurry to reach safer parts. All tuna, even the jig-shy bluefin, will bite it, and so will marlin, wahoo, yellowtail, bonito, dorado, grouper, cabrilla, snapper and ambitious mackerel. We put a cedar plug behind the boat with four hot, skirted jigs from different makers. For two days, the plug caught as many tuna (mostly albacore, but we trolled up yellowfin and some bluefin as well) as the rest of the jigs put together, no matter if it was fished in the corners or in the middle of the stern. We alternated location after each fish-producing stop.

We put a cedar plug behind the boat with four hot, skirted jigs from different makers. For two days, the plug caught as many tuna (mostly albacore, but we trolled up yellowfin and some bluefin as well) as the rest of the jigs put together, no matter if it was fished in the corners or in the middle of the stern. We alternated location after each fish-producing stop. We can hope this year for another bluefin bite like we experienced over the past three seasons, each of which was better than the previous one. Last year was the best I can remember for shortfin. But even if the water warms so fast and so much this year that bluefin and their cool-water brethren the albacore make an early departure, you’ll still be making a smart move to bag yellowfin tuna or dorado, if you pull a cedar plug along with your Zukers and other trolling jigs.

We can hope this year for another bluefin bite like we experienced over the past three seasons, each of which was better than the previous one. Last year was the best I can remember for shortfin. But even if the water warms so fast and so much this year that bluefin and their cool-water brethren the albacore make an early departure, you’ll still be making a smart move to bag yellowfin tuna or dorado, if you pull a cedar plug along with your Zukers and other trolling jigs. The New 34 – Clean Lines and Built to Tackle Any Gamefish

The New 34 – Clean Lines and Built to Tackle Any Gamefish The Regulator 34 is 33 feet, 10 inches LOA with a 10-foot, 11-inch beam. When sitting on the helm seat looking forward this boat seems much larger than other center consoles in its class. There is something about a Carolina-flared bow and a wide beam that just make these boats feel much roomier than the other production boats. The transom area is squared up and roomy enough for three or four guys to be pulling on fish. The outboard bracket that doubles as a swim step opens up the cockpit area with a large oval live bait tank centered on the transom gunnel and a 272 quart fish box for chilling a boat load of gamefish on the port transom. The only thing I would change for our West Coast-style fishing is a removable bait tank lid instead of the hatch that folds open for easy access. On the starboard side there is a dive door much like the lifeguard boats but with a secure hatch that folds down onto the transom. For the diving community this is a huge plus—as well as for that once-in-a-lifetime goal of loading a swordfish or giant tuna onto the deck.

The Regulator 34 is 33 feet, 10 inches LOA with a 10-foot, 11-inch beam. When sitting on the helm seat looking forward this boat seems much larger than other center consoles in its class. There is something about a Carolina-flared bow and a wide beam that just make these boats feel much roomier than the other production boats. The transom area is squared up and roomy enough for three or four guys to be pulling on fish. The outboard bracket that doubles as a swim step opens up the cockpit area with a large oval live bait tank centered on the transom gunnel and a 272 quart fish box for chilling a boat load of gamefish on the port transom. The only thing I would change for our West Coast-style fishing is a removable bait tank lid instead of the hatch that folds open for easy access. On the starboard side there is a dive door much like the lifeguard boats but with a secure hatch that folds down onto the transom. For the diving community this is a huge plus—as well as for that once-in-a-lifetime goal of loading a swordfish or giant tuna onto the deck. The port side entry door leads down into what I would call the master stateroom. I am 5-foot-9 and had plenty of room overhead–at least another foot or more. The fresh-water sink and head are set into a beautiful Corian countertop. Behind the Corian counter is a cabinet with easy access to the electronic panels and battery terminals. The vee berth sleeps two very comfortably with LED lights and several storage compartments for personal belongings. The console vee berth would be an ideal place to keep fishing outfits locked up after a trip, and this particular model had a vertical rod rack for additional storage. Being able to store your fishing outfits on a center console is a HUGE time saver and keeps anglers from having to make multiple trips up and down the dock loading gear.

The port side entry door leads down into what I would call the master stateroom. I am 5-foot-9 and had plenty of room overhead–at least another foot or more. The fresh-water sink and head are set into a beautiful Corian countertop. Behind the Corian counter is a cabinet with easy access to the electronic panels and battery terminals. The vee berth sleeps two very comfortably with LED lights and several storage compartments for personal belongings. The console vee berth would be an ideal place to keep fishing outfits locked up after a trip, and this particular model had a vertical rod rack for additional storage. Being able to store your fishing outfits on a center console is a HUGE time saver and keeps anglers from having to make multiple trips up and down the dock loading gear. If I had to build a West Coast center console in the 34-foot range set up to tackle any Pacific gamefish, I would save myself the time, money and effort and just call Pete Giacalone at Kusler Yachts. The Regulator 34 is “that” boat plus it is set up just right for family and friends to enjoy boating along with a safe and smooth ride. Pete can be reached at (619) 992-8194 or by email at pete@kusleryachts.com.

If I had to build a West Coast center console in the 34-foot range set up to tackle any Pacific gamefish, I would save myself the time, money and effort and just call Pete Giacalone at Kusler Yachts. The Regulator 34 is “that” boat plus it is set up just right for family and friends to enjoy boating along with a safe and smooth ride. Pete can be reached at (619) 992-8194 or by email at pete@kusleryachts.com.